Life is about being as mindful, persistent and resilient as we can be, all the while remembering that forces beyond our control play an important role in any outcome. I would bet to many that strokes are a “bad” thing. I’m not so sure. I’m learning that labeling things good and bad can limit our ability to learn from them. Strokes, therefore, like everything else in life, are primarily an opportunity to grow understanding, compassion, and kindness.

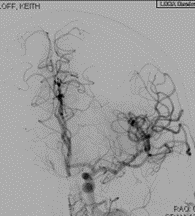

Time is brain. Every hour your brain is deprived of oxygen and blood, it ages 3.5 years. So, I have to live with the fact that I now have a 79-year-old brain inside my almost 65-year-old body. Not complaining, just grateful to be alive and still wearing a white shirt every Monday. Here’s what my brain looked when I arrived in the ER (image on left, with circle showing clot), and how it looked hours later (image on right, with blood flow restored).

Speech at the 2013 Heart Walk Association in Rochester, NY.

Hello, I’m Keith Nickoloff, and I’m a walking miracle.

As a walking miracle, I’m one of the many voices here today to celebrate the exceptional resources of heart and stroke care that exist in our community. Naturally, I’m grateful to be a walking miracle. For one thing, it means being alive. For another, I’ve been blessed with an ever-deeper reverence for life … which I will say more about presently. But the reason I’m here today is to help make walking miracles like me a thing of the past. Or perhaps a better way to put it is I want to make walking miracles like me much more commonplace, much more ordinary, much more every day. And this will happen, most assuredly, as Rochester continues on the path of being a world-class center for the treatment of heart disease, strokes and other cardiovascular challenges.

My neuro-surgeon, Dr. Babak Jahromi, tells me he foresees the day when Rochester, New York is as famous for the treatment of strokes as Rochester, Minnesota, home of the Mayo Clinic, is for the treatment of rare medical problems.

I’m living proof that we’re on our way.

It’s a Monday evening in July 2011, just eighteen months ago. An hour or so earlier I’m having a drink with colleagues after playing in a company softball game. My teammates noticed that I was acting strange, knew enough to suspect a stroke, and called 911. Now I’m in the loving care of the Strong stroke team. They’re asking me to do things: raise my arms; smile; stick out my tongue; squeeze their fingers. I think I’m following their instructions perfectly. I don’t realize the right side of my body isn’t moving. I don’t realize the right side of my face looks like a balloon that’s been left in the sun too long.

Curiously, I don’t know exactly what’s going on, but whatever it is I’m in no pain. In fact, it’s quiet, it’s still. I’m strangely at peace.

My family, meanwhile, is in shock. They’re learning that I might very well die in the next few hours. They’re learning that 40 percent of my brain has been fried. They’re learning that if I do survive I will most likely be in a nursing home rehabbing for a number of years. They’re learning that the clot-buster drug the doctors administered didn’t work. And they’re learning that pretty much my only shot at making it is a high-risk surgery that might make my condition worse – might even kill me – and it must happen as quickly as possible.

The following morning, Tuesday, my brain is working well enough for me to know that I can’t remember my wife’s name. I think to myself: if can’t remember that, I better not say anything to anybody. So I spent the whole day silent.

The morning after that, however, Wednesday 5 A.M., I’m awoken from sleep by a sudden surge of neuron re-connection – a brain re-boot, if you will. I not only remember my wife’s name, but I can also carry on a conversation –– in a certain helter-skelter way. My ability to retrieve the precise word leaves a lot to be desired. As does my ability to put words in exactly the right order. But no matter. People grasp the gist of what I’m saying, and I’m told there’s every reason to assume my ability to speak will improve over time.

I certainly have no problem later that morning communicating to Dr. Jahromi’s right hand, Cindy Zink, that I feel good enough to walk. She says let’s go. In short order I’m zipping around the hallways. Eventually, we pass some stairs and Cindy says, “You want to give them a go? I say yes. I walk up the stairs; I walk down the stairs. Twice. And I know I must be doing pretty well because by this point Cindy is tearing up.

That’s Wednesday, not 48 hours after the stroke. I’m now scheduled to be discharged two days later, Friday, but a little infection and the need to get my meds adjusted “just right” keeps me in the hospital until the following Monday.

So there you have it. Monday, one week after suffering a stroke that could have crippled me if not killed me––and, in fact, does cripple or kill most people––I walk into my office on the way home from the hospital. There I greet my colleagues. With deep gratitude, I thank those I had that drink with a week earlier for being a big reason I’m still here.

Dr. Jahromi told me, “Keith, at present, I’ve experienced only a handful of outcomes like yours. And no one has been restored as quickly as you.”

His comment is why I call myself a walking miracle. And why, like you, I’m here to help all those who are attempting to make walking miracles like me the expectation, not the exception.

How does this happen?

If my experience is any indication, there are at least three factors that contribute to the effective treatment of a stroke.

One, medical expertise. Two, the knowledge of average citizens. And three, what you can call just plain luck or what I call the grace of God. Without all three, I wouldn’t be here.

Just how much the Rochester heart and stroke community can be influenced by the Almighty you can decide for yourself, but when it comes to growing medical expertise as well as the knowledge base of the general public, the intention is to be a servant second to none. Supporting that intention is the reason we’re gathered here this morning.

From the minute my colleagues’ 911 call was received––all the way to this very moment––the outstanding collective medical intelligence related to the care of strokes that this community enjoys has given me an excellent chance at a healthy life.

And there has been a bump or two along the way. Such as, a few months after my stroke, the development of an aneurysm –– resulting from the original trauma to my carotid artery. Another Dr. Jahromi and Cindy Zink surgery was needed to fix the aneurysm before it killed me. Today I carry a lovely stent in my neck.

I’m very aware that the healthy life I have wouldn’t have been possible if one of my colleagues––not a medical professional at all––hadn’t been savvy enough to recognize the signs of a stroke. And, just as important, he knew to call 911 rather than drive me to the hospital himself.

That point, by the way, is a good example of the knowledge we in this room want the world to have: the understandable human impulse to race a suddenly ill person to the hospital ourselves, rather than wait for the EMT’s to manage it, is among the reasons many stroke victims don’t get the attention they need as quickly as they need it. And in the world of strokes, time is brain.

It’s pretty humbling to appreciate that, no matter how knowledgeable my colleagues were, or how alert the EMT’s, or how skilled the Strong stroke team…all of that may not have been enough to keep me alive. There was still the X-factor, or as I experience it, the will of God.

My stroke took place in a sports bar as I was attempting to sign the check for that traditional after-game single round of drinks with my colleagues. Before joining them in the bar, I was in the parking lot having an enjoyable 10 minute phone conversation with my son in Denver. Now if I hadn’t had that conversation, our drinking time might have ended 10 minutes earlier. I might have had my stroke while driving myself home. Imagine the harm I could have caused others. Or maybe I would have made it home and had my stroke there, a sobering thought since I would have been alone for who knows how long. My wife was spending that entire week at a church conference four hours away.

I’m alive today because countless vital factors coalesced at a given moment in time––and it’s just possible that one of the most important of them was sitting in my car for 10 minutes connecting with my son.

I tell this story because it helps me remember one of life’s great lessons, and one that surely applies to making Rochester the best heart and stroke center possible. Life is about being as mindful, persistent and resilient as we can be, all the while remembering that forces beyond our control play an important role in any outcome.

I’d like to conclude by sharing a very personal reflection on how my stroke has been a powerful teacher––how it has enriched my reverence for life.

The knee-jerk reaction of most of us, I would bet, is that strokes are a “bad” thing. I’m not so sure. I’m learning that labeling things good and bad can limit our ability to learn from them. Strokes, therefore, like everything else in life, are primarily an opportunity to grow understanding, compassion, and kindness.

One small piece of understanding I’d like to share because it might save someone else’s life is what specifically triggered my stroke in the first place.

I’m what you might call a gentleman farmer.

This means my wife and I have land, livestock, horses and assorted farm equipment; it’s a labor of love. We’re fortunate that one of our daughters and her family, including three young grandsons, live on 10 acres across the road from us.

In the two weekends prior to my stroke, I spent many hours on our tractor bush-hogging a creek bed on my daughter’s land to expand the space where her children could play. (A bush-hog, for those unfamiliar with the term, is basically a mower on steroids pulled by a tractor to mow fields.) Anyway, the mowing I did around the creek bed caused me to continually go forward-and-reverse, forward-and-reverse. And since I had to watch where I was going, I spent many hours turning my head over my right shoulder back-and-forth, and back-and-forth. What I learned the hard way is that repetitive motion like this (painting a ceiling might be another example) can either cause or contribute to trauma to the carotid artery.

Sunday afternoon I’m bush hogging, waving goodbye to my wife as she drives off to her conference. Monday evening I’m having my life saved.

While growing kindness, compassion and understanding may be the ultimate gift of life, that growing can include the pain of a lot of losses.

I’ve lived with the possibility that I might never be able to pick up my six grandchildren again, or ride or care for our horses as I have. That uncertainty went on for a year before Dr. Jahromi said the magic words this past June: “Keith, you’re as good as new; go forth as if this never happened.”

Nice to hear, but I have to be honest; I’m still careful belting out hymns at church, and am mindful to sneeze as gently as I can.

Not only that, but the tool I use most effectively to navigate the world––my ability to speak extemporaneously––has been compromised, and may remain so forever. My right hand, the hand I write with, cramps up regularly. I write and type like a beginner. My right foot drags when I get tired each night.

My family looks at me differently, and may always do so. Their pain of almost losing me, and their fear of another stroke (that at any moment I might be gone) is part of my life now, as well.

But with this pain, with these losses, is also an awareness quite beautiful.

For instance: I realize that, without even trying to be, I am a flesh and blood reminder to my loved ones not to take any moment of life for granted. Anytime I reflect on how this reminder can serve them throughout their lives, as it serves me, I am deeply grateful. And if having a stroke was the price I had to pay for those I love to have that reminder printed indelibly on their heart, I’m happy to pay it.

Let me end with my favorite story about how my life has changed.

A month or so after my stroke, I’m having breakfast as I have done for pretty much the entire 32 years of my marriage. My wife, Lori, and I are sitting across the table from one another. I’m eating oatmeal, as I always do. And I’m eating it just as fast as I can, as I always do, because, as everyone who knows me can tell you, I’m a man in a hurry. And because I’m a man in a hurry, I’m not only eating, I’m also reading the day’s newspaper.

This is how it is every single morning.

On this particular morning, as sometimes happens, Lori asked me a question, or made some comment of some kind. Then, as usually happens, without pausing either my eating or reading, I looked at her with one eye and grunted. Being a dutiful husband, when I finished my oatmeal, I washed the dish, kissed her goodbye, hopped in the car, and sped off to work. Only, on this particular day, a month after my stroke, I sped all of about 10 feet. Then I stopped, turned off the car, went back into the house… and apologized to Lori for not being present. “I want to give you my full attention,” I said. That day I cancelled my newspaper subscription. Time will tell whether oatmeal is next.

Thank you for the privilege of being here today. May God bless and keep you.

Take The First Step

If you’re not thinking about your print strategy holistically, you may be paying millions of dollars more every year than needed. However, developing a strategy and utilization of fixed assets can lead to an enterprise saving between 35-65%.

If you are interested in these types of savings and driving bottom-line impact, the model below is how and what PathForward does in helping organizations like yours find the best-tailored strategy for their goals, priorities, and requirements.

We have helped organizations like yours save over $750M.